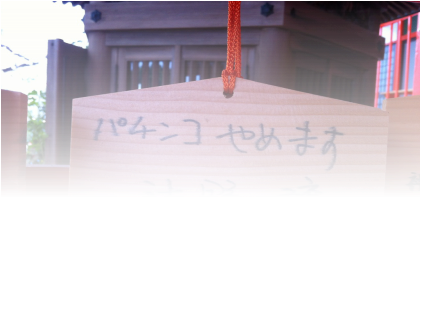

A prayer request at Naritasan temple in order to stop gambling at pachinko.

The name has been obscured to protect privacy.

The name has been obscured to protect privacy.

If I die and go to hell, I am quite certain it will resemble the inside of a Japanese pachinko parlor. There is the noise of thousands of steel balls slamming into bumpers and pins. The screech of the megaphoned announcers is often deafening. The air is so thick with cigarette smoke that you could cut it with a knife. The garish shag carpeting is as loud as it is scarred from burn holes. Patrons’ faces express alternating measures of compulsion and remorse for their gambling. Thousands of ball bearings fill plastic trays behind the lucky, creating a tripping, slipping, and fire-exit hazards. There is the seedy feel of a business designed with the gaudy flair of a low-level yakuza.

In fact, you might say that the look and feel of these places is roughly the opposite of all the wonderful virtues of traditional Japanese aesthetics. (image credit)

In fact, you might say that the look and feel of these places is roughly the opposite of all the wonderful virtues of traditional Japanese aesthetics. (image credit)

Is there a Mrs. Pachinko?

Yet, despite my personal aversion, pachinko is truly a Japanese institution. By some estimates, as much as 25% of all money spent on recreation in Japan is paid out for pachinko. Within 200 meters of our house there are four large parlors, sporting a variety of themes. Regulars line up 30 deep in front of the buildings as much as an hour before they open at 10:00 AM. They jockey for the machines that they have intimately come to know, before the pins are invariably reset and their playing advantages are lost.

It is somewhat reassuring that pachinko's popularity has been on a steep decline in the last ten years or so. Lack of disposable income combined with healthier living seems to have dealt something of a one-two punch to vertical-pinball.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed